Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (French: affaire Dreyfus) was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent. Sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly having communicated French military secrets to the German Embassy in Paris, Dreyfus was sent to the penal colony at Devil's Island in French Guiana and placed in solitary confinement.

Two years later, in 1896, evidence came to light identifying a French Army major named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real culprit. However, high-ranking military officials suppressed this new evidence and Esterhazy was unanimously acquitted after the second day of his trial in military court. Instead of being exonerated, Alfred Dreyfus was further accused by the Army on the basis of false documents fabricated by a French counter-intelligence officer, Hubert-Joseph Henry, seeking to re-confirm Dreyfus's conviction. These fabrications were uncritically accepted by Henry's superiors.[1]

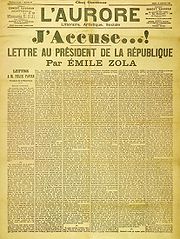

Word of the military court's framing of Alfred Dreyfus and of an attendant cover-up began to spread largely due to J'accuse, a vehement public open letter in a Paris newspaper by writer Émile Zola, in January 1898. The case had to be re-opened and Alfred Dreyfus was brought back from Guiana in 1899 to be tried again. The intense political and judicial scandal that ensued divided French society between those who supported Dreyfus (the Dreyfusards[2]), such as Anatole France, Henri Poincaré or Georges Clémenceau, and those who condemned him (the anti-Dreyfusards), such as Edouard Drumont (the director and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper La Libre Parole) and Hubert-Joseph Henry.

Eventually, all the accusations against Alfred Dreyfus were demonstrated to be baseless. Dreyfus was exonerated and reinstated as a major in the French Army in 1906. He later served during the whole of World War I, ending his service with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

| This article is part of the Dreyfus affair series. |

| Investigation and arrest |

| Trial and conviction |

| Picquart's investigations |

| Other investigations |

| Public scandal |

| "J'accuse...!" - Zola |

| Resolution |

| Alfred Dreyfus |

Contents |

Investigation and arrest

Trial and conviction

Picquart's investigations

While Alfred Dreyfus was serving his sentence on Devil's Island back, supporters and the press in France began to question his guilt. The most notable of these was Major Georges Picquart, who brought evidence of forged evidence to his superiors and, when ordered to keep silent, leaked information to the Dreyfusard press. Picquart was later court martialed for his revelations. After Dreyfus was exonerated, Picquart was also cleared and restored to his military position.

Other investigations

After Major Georges Picquart's exile to Tunisia others took up the cause of the Alfred Dreyfus.

Public scandal

The debate over falsely accused Alfred Dreyfus grew into a public scandal of unprecedented scale, and caused most of the French nation to become divided between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards.

Émile Zola's open letter

The influential writer Émile Zola wrote an open letter published on January 13, 1898, in the newspaper L'Aurore. The letter was addressed to President of France Félix Faure, and accused the government of anti-Semitism and the unlawful jailing of Alfred Dreyfus, a French General Staff officer sentenced to penal servitude for life for espionage. Zola pointed out judicial errors and lack of serious evidence. The letter was printed on the front page of the newspaper, and caused a stir in France and abroad. Zola was prosecuted and found guilty of libel on 23 February 1898. To avoid imprisonment, he fled to England, returning home in June 1899.

Other pamphlets proclaiming Dreyfus's innocence include Bernard Lazare's A Miscarriage of Justice: The Truth about the Dreyfus Affair (November 1896).

Resolution

Aftermath

The affair saw the emergence of the "intellectuals" — academics and others with high intellectual achievements who took positions on grounds of higher principle — such as Émile Zola, novelists Octave Mirbeau and Anatole France, mathematicians Henri Poincaré and Jacques Hadamard, and Lucien Herr, librarian of the École Normale Supérieure. Constantin Mille, a Romanian socialist writer and émigré in Paris, described the anti-Dreyfusard camp as a "militarist dictatorship".[3]

Alfred Dreyfus after the Dreyfus Affair

Alfred Dreyfus was reinstated into the French Army, re-promoted to his prior rank of Major, and made a Chevalier of the French Légion d'honneur in July 1906.[4] However, his health had deteriorated during his imprisonment on Devil's Island and, on his request, he was granted an honorable discharge in 1907. In 1908, at the burial of Zola at the Panthéon, he was slightly wounded in an assassination attempt. Célestin Hennion, the head of the French Police, was on-hand to arrest the would-be assassin, who was tried but found innocent.

Dreyfus volunteered for military service again in 1914, at the beginning of World War I, serving despite advancing age in a wide range of artillery commands, as a major and finally as a lieutenant-colonel. He was raised to the rank of Officer of the Légion d'honneur in 1919.[5] His son, Pierre Dreyfus, also served in World War I as an artillery officer and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Alfred Dreyfus' two nephews also fought as artillery officers in the French Army during World War I but both lost their lives. The same artillery piece secrets of which Dreyfus was accused of revealing to the Germans was used in blunting the early German offensives because of its ability to maintain accuracy during rapid fire.

Dreyfus died two days before Bastille Day in 1935. His funeral cortège passed through ranks assembled for Bastille Day celebrations at the Place de la Concorde, and he was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery.

Political ramifications

The factions in the Dreyfus affair remained in place for decades afterward. The far right remained a potent force, as did the moderate liberals. The liberal victory played an important role in pushing the far right to the fringes of French politics. It also prompted legislation such as a 1905 law separating church and state. The coalition of partisan anti-Dreyfusards remained together, but turned to other causes. Groups such as Maurras's Action Française, formed during the affair, endured for decades.

The Vichy Regime was composed to some extent of old anti-Dreyfusards and their descendants. The Vichy Regime would later close its eyes to the arrest of Dreyfus's granddaughter, Madeleine Levy, by the Gestapo. Madame Levy was imprisoned in Camp Drancy on November 3, 1943, and on November 20 of the same year she was deported to Auschwitz, where she perished.[6]

Antisemitism and birth of Zionism

The Hungarian-Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl had been assigned to report on the trial and its aftermath. Soon afterward, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State, 1896) and founded the World Zionist Organization, which called for the creation of a Jewish State in Palestine. The antisemitism and injustice revealed in France by the conviction of Alfred Dreyfus had a radicalizing effect on Herzl, persuading him that Jews, despite the Enlightenment and Jewish assimilation, could never hope for fair treatment in European society. While the Dreyfus affair was not Herzl's initial motivation, it did much to encourage his Zionism.

In the Middle East, the Muslim Arab press was sympathetic to the falsely accused Captain Dreyfus, and criticized the persecution of Jews in France.[7]

Not all Jews saw the Dreyfus Affair as evidence of antisemitism in France, however. It was also viewed as the opposite. The Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas often cited the words of his father: "A country that tears itself apart to defend the honor of a small Jewish captain is somewhere worth going."[8]

Commission of sculpture

In 1985, President François Mitterrand commissioned a statue of Dreyfus by sculptor Louis Mitelberg. It was to be installed at the École Militaire, but the Minister of Defense refused to display it, even though Alfred Dreyfus had been rehabilitated into the Army and fully exonerated in 1906. Today it can be found at Boulevard Raspail, n°116-118, at the exit of the Notre-Dame-des-Champs metro station. A replica is located at the entrance of the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris.

Centennial commemoration

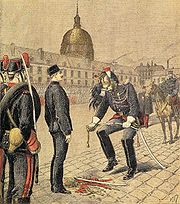

On 12 July 2006, President Jacques Chirac held an official state ceremony marking the centenary of Dreyfus's official rehabilitation. This was held in the presence of the living descendants of both Émile Zola and Alfred Dreyfus. The event took place in the same cobblestone courtyard of Paris's École Militaire, where Capitaine Dreyfus had been officially stripped of his officer's rank. Chirac stated that "the combat against the dark forces of intolerance and hate is never definitively won," and called Dreyfus "an exemplary officer" and a "patriot who passionately loved France." The French National Assembly also held a memorial ceremony of the centennial marking the end of the Affair. This was held in remembrance of the 1906 laws that had reintegrated and promoted both Dreyfus and Picquart at the end of the Dreyfus Affair.

Tour de France and L'Auto

The roots of both the Tour de France bicycle race and the daily sporting newspaper L'Auto (now L'Équipe) can be traced to the Dreyfus Affair. Le Velo, then the largest sports daily in France, was Dreyfusard. In 1900 a group of anti-Dreyfusards started L'Auto to compete with Le Velo. L'Auto in turn created the Tour de France race in 1903. [9]

The trigger for these events was a brawl between Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards at the Auteuil racetrack in Paris in 1899. In this incident, the President of France, Émile Loubet, was struck on the head with a walking stick by Count Albert de Dion, owner of the De Dion-Bouton motor car company. [10]

De Dion served 15 days in jail and was fined 100 francs. De Dion's behavior was savagely criticised by Le Vélo and its Dreyfusard editor, Pierre Giffard. De Dion responded by starting L'Auto. He was supported by other wealthy anti-Dreyfusards such as Adolphe Clément and Edouard Michelin. (They were also concerned with Le Vélo because its publisher was their rival, Automobiles Darracq SA.)[11]

L'Auto was not the success its backers wanted. By 1903, its circulation was declining. To boost its circulation, L'Auto launched a new long-distance bicycle race, with distances and prizes far exceeding any previous race. This was the Tour de France.[12]

Portraits of the affair in various media

- Literature

- The Dreyfus Centenary Bulletin, London/Bonn 1994; The Dreyfus Centenary Committee.

- The Dreyfus affair plays an important part in In Search of Lost Time, by Marcel Proust, especially Vols. 3 and 4.

- L´Affaire en Chanson, 1994 by George R. Whyte; Paris Bibliotheque de documentation internationale contemporaine BDIC; Paris, Flammarion.

- A satirical take on the Dreyfus affair appears in L'ile Des Pingouins by Anatole France.

- The Dreyfus Affair is mentioned several times in The Children's Book by A.S. Byatt.

- The Dreyfus Trilogy by George R. Whyte, Inter Nationes, 1996.

- The Dreyfus Affair, A Chronological History by George R. Whyte, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006

- Admission is not Acceptance – Reflections on the Dreyfus Affair. Antisemitism. George R. Whyte. London Valentine Mitchell, 2007; Paris Editions Le Manuscript/Unesco 2008, Buenos Aires Lilmod 2009, Moscow Xonokoct, 2010.

- Theatre

- Seymour Hicks wrote a drama called One of the Best, based on the Dreyfus trial, starring William Terriss. It played at the Adelphi Theatre in London in 1895. The idea was suggested to Hicks by W.S. Gilbert.

- AJIOM/Captain Dreyfus, Musical. Music and text by George R. Whyte, 1992

- The Dreyfus Trilogy by George R. Whyte (in collaboration with Luciano Berio, Jost Meier and Alfred Schnittke) comprising the opera "Dreyfus-Die Affäre" (Deutsche Oper Berlin, 8. May 1994; Theater Basle, 16. October 1004; "The Dreyfus Affair" New York City Opera, April 1996); the dance drama "Dreyfus-J´accuse´" (Oper der Stadt Bonn, 4. September 1994) and the musical satire Rage et Outrage (Arte, April 1994; Zorn und Schande, Arte 1994; Rage and Outrage Channel 4, May 1994.

- "Dreyfus Intme" by George R. Whyte, Opernhaus Zurich, December 2008; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, may 2009. Also in German, English, French, Hungarian, Hebrew and Czech.

- Films

- The court proceedings on the Dreyfus affair were the first to be documented in cinema.[13]

- L'Affaire Dreyfus, Georges Méliès, Stumm, France, 1899

- Trial of Captain Dreyfus, Stumm, USA, 1899

- Dreyfus, Richard Oswald, Germany, 1930

- The Dreyfus Case, F.W. Kraemer, Milton Rosmer, USA, 1931

- The Life of Emile Zola, USA, 1937

- I Accuse!, José Ferrer, England, 1958

- Prisoner of Honor, directed by Ken Russell, historical advisor George R. Whyte, focuses on the efforts of Colonel Picquart to have the sentence of Alfred Dreyfus overturned. Colonel Picquart was played by American actor Richard Dreyfuss, who "grew up thinking that Alfred Dreyfus and [him] are of the same family."[14] USA, 1991

- L'Affaire Dreyfus (released in Germany as Die Affäre Dreyfus), Yves Boisset, 1995

- Radio

- BBC Radio J'Accuse, UK, Hattie Naylor. Radio dramatisation inspired by a newspaper article written by Emile Zola in response to the Dreyfus Affair of the 1890s.

BBC Radio 4, broadcast on 13 Jun 2009

- L´Affaire Dreyfus´, interview with George R. Whyte, France Culture, 25. March 1995

- J´accuse, George R. Whyte, Canadian Broadcasting Service (CBS), 10. October 1998

- The Dreyfus Affair, interview with George R. Whyte, BBC Radio 3. By John Pilgrim, 28 October 2005.

- Television

- The Time Tunnel episode Devil's Island. Story in which Drs. Newman & Phillips encounter Captain Dreyfus, newly arrived on Devil's Island.

ABC, broadcast on 11 Nov 1966

- Dreyfus in Opera and Ballet/The Odyssey of George Whyte, September 1994, WDR, Swedish, Hungarian and Finnish television.

- Rage and Outrage- a musical satire by George R. Whyte, broadcast on Arte and Channel 4, May 1994.

- Dreyfus-J’Accuse Dance drama by George Whyte. Oper der Stadt Bonn, 4. September 1994. WDR, Sweden STV1, Slovenia RTV, SLO, Finland YLE.

- Radio Discussion

- BBC Radio 4, October 8 2009, In Our Time, The Dreyfus Affair Downloadable discussion on BBC Radio 4. Melvyn Bragg; Robert Gildea, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University; Ruth Harris, Lecturer in Modern History at Oxford University; Robert Tombs, Professor of French History at Cambridge University.[15]

- New Books in History, June 17 2010, podcast interview with Ruth Harris about her book Dreyfus: Politics, Emotion, And the Scandal of the Century (2010)

See also

- Antisemitism

- Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy the true perpetrator of the crime of which Alfred Dreyfus had been wrongly accused and convicted.

- History of Jews in Alsace

- Dreyfus Society for Human Rights

- George R. Whyte and The Dreyfus Affair

Notes

- ↑ See, for example, Jean-Denis Bredin, The Affair: the Case of Alfred Dreyfus. (New York: George Braziller, 1986).

- ↑ The term post-dates the start of the affair.

- ↑ (Romanian) Constantin Antip, "Émile Zola: «Adevărul este în marş»" ("Émile Zola: «Truth Is Marching On»"), in Magazin Istoric

- ↑ Minutes of the induction of Dreyfus into the Legion of Honor, French Ministry of Culture and Communication, Culture.fr

- ↑ Alfred Dreyfus: Chronology, French Ministry of Culture and Communication, Culture.fr

- ↑ George R. Whyte, The Dreyfus affair: a chronological history, Basingstoke 2008, p 331

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard (1986). Semites and Anti-Semites. Pg. 133

- ↑ Secularism, the French & Alfred Dreyfus - July 7, 2006 - The New York Sun

- ↑ Harp, Stephen L. (2001). Marketing Michelin: Advertising & Cultural Identity in Twentieth-Century France. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 20. ISBN 0-8018-6651-0.

- ↑ Weber, Eugen (2003), "Foreword", The Tour de France, 1903-2003: a century of sporting structures, meanings and values, London: F. Cass, p. xi, ISBN 0-7146-5362-4

- ↑ Boeuf, Jean-Luc; Léonard, Yves (2003). La République de Tour de France. Paris: Editions du Seuil. p. 23. ISBN 9782020580731.

- ↑ Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991). Le Tour: the rise and rise of the Tour de France. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9780340542682.

- ↑ Yosef Lang. The Life of Eliezer Ben Yehuda. Yad Yitzhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem 2008. p. 373.

- ↑ Brozan, Nadine. Chronicle. New York Times. 20 November 1991.

- ↑ BBC Radio 4, October 8 2009, In Our Time - The Dreyfus Affair, Melvyn Bragg; Robert Gildea, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University; Ruth Harris, Lecturer in Modern History at Oxford University; Robert Tombs, Professor of French History at Cambridge University.

References

- General Andre Bach, 2004, "L'Armée de Dreyfus. Une histoire politique de l'armée française de Charles X a l'"Affaire". Tallandier,Paris, ISBN 2-84734-039-4

- Pierre Birnbaum,1998,"L'Armée Française était elle antisemite?", pp 70–82 in Michel Winock: "L'Affaire Dreyfus", Editions du Seuil, Paris, ISBN 2-02-032848

- Jean-Denis Bredin, 1986, "The Affair: the Case of Alfred Dreyfus." George Braziller, New York, ISBN 0-8076-1175-1

- Jean Doise, 1984, "Un secret bien gardé. Histoire militaire de l'Affaire Dreyfus." Editions du Seuil, Paris, ISBN 2-02-021100-9

- Vincent Duclert,2006,"Alfred Dreyfus",Librairie Artheme Fayard,ISBN 2 213627959

- George R. Whyte, The Accused -The Dreyfus Trilogy, Inter Nationes 2006, ISBN 3-929979-28-4

- Adam Kirsch (July 11, 2006), The Most Shameful of Stains, The New York Sun

- Stanley Meisler (July 9, 2006), Not just a Jew in a French jail, The Los Angeles Times

- Ronald Schechter (July 7, 2006), The Ghosts of Alfred Dreyfus, The Forward.

- George R. Whyte, The Dreyfus Affair - A chronological history, Palgrave Macmillan 2008, ISBN 13: 978-0-230-20285-6

- Kim Willsher (June 27, 2006), Calls for Dreyfus to be buried in Panthéon, The Guardian

- Pierre Touzin et Francois Vauvillier,2006, "Les canons de la Victoire 1914-1918.Tome1. L'artillerie de campagne". Histoire et Collections, Paris.ISBN : 2-35250-022-2

Further reading

- (English) (French) 1906 : Dreyfus rehabilitated. Site of the French Ministry of Culture

- (French) Site of the National Assembly

- Oscar Wilde and the Dreyfus Affair from Victorian Studies, Vol. 41, 1

- Text of J'accuse! (in French)

- Text of J'accuse! (in English and French)

- Alfred Dreyfus and "The Affair"

- America's Dreyfus Affair, by David Martin

- Complete Digital Bibliography on CD-ROM

- Greatest Newspaper Article of all Time (Journalistic retrospective of Zola's "J'accuse!")

- Prisoner of Honor at the Internet Movie Database

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - Andre Cremieu-Foa

- Temporal and Eternal by Charles Péguy, translated by Alexander Dru

- The Life of Emile Zola at the Internet Movie Database

- Jean-Denis Bredin, The Affair: The Case of Alfred Dreyfus (1986), ISBN 0-8076-1175-1

- George R. Whyte, The Dreyfus Affair – A Chronological History, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, ISBN 13: 978-0-230-20285-6

- Anya Rous The Rising Celebrity and Modern Politics—The Dreyfus Affair